An overview of the National Memorial Museum of Forced Mobilization under Japanese Occupation in the southern port city of Busan. [Photo by Lee Seung-Jae]

(This column was contributed by Lee Seung-jae, an Aju Business Daily editorial writer.)

SEOUL -- Yoyi Tang! (ようい,どん!)...Japan's declaration of economic war is imminent. It is a declaration of war that the Japanese government deliberates and approves revisions to an export control ordinance to remove South Korea from a whitelist of countries list at the Cabinet meeting, the same as our State Council.

After Japan heralded a declaration of war on July 4, saying it would strengthen regulations on exports of key semiconductor materials to South Korea, we've come to know all of a long time that we did not know about Japan. We are seeing again the true nature of Japan. Only when we study Japan properly, we can get to know Japan better (Know Japan), and then we can take advantage of Japan better (Use Japan) and move on to overcome Japan (Overcome Japan). This three-step strategy against Japan will apply equally to each Korean citizen as well as to our nation and businesses. The simple structure of pro-Japan and anti-Japan is worn out quite a while. Rather than help fight, it only cultivates a cancer cell of 'internal division.'

To know Japan at this level starts from grasping exactly atrocities committed by Japan against us. It is a shameful story, but I did not know that there was a foundation headed by Chairman Kim Yong-deok to support the victims of forced labor under Japan's colonial rule as a public institution under the Ministry of the Interior and Safety. Moreover, I have learned for the first time that it has been four years since the National Memorial Museum of Forced Mobilization under Japanese Occupation, run by the foundation, opened its doors in Busan.

On July 24, I headed to Busan on a KTX (Korea Train Express) to visit the memorial museum and blamed myself for ignorance while reading data on Japan's forced labor. Even when I met and talked with officials from the foundation and the memorial museum, I felt uncomfortable and heartbroken all the while as a Korean citizen, thinking "Why have we neglected such history?"

-- Forced labor, the hardship of grass roots who have been shunned --

The museum, which opened in December 2015, is the 41st national museum in South Korea. It was built at a cost of 52.2 billion won ($43.8 million) to let the public know the horrors of forced labor committed by the Japanese imperialists and to have a proper sense of history. It was built in Busan because as much as 22 percent of people forced into labor during Japan's colonial occupation came from Gyeongsang provinces, with many of them making tearful parting at the Busan port. It is located in the special U.N. zone for peace and culture in Daeyeon-dong, Nam-gu, Busan, which has the world's only UN Memorial Cemetery (state-designated cultural property).

Initially, the memorial museum was to be built at the Independence Hall in Cheonan, South Chungcheong Province, but there were complaints that independent fighters and those forced into labor are different. The reason why famous politicians and dignitaries have never visited it is also in line with the distorted perception and low assessment of grass roots who were forced into labor.

Because of the current situation, the number of visitors has increased somewhat. "From the time I made plans for my vacation in Busan, I planned to stop by the memorial museum," said a household head in his 40s, who came from a new town in Gyeonggi Province to Busan for a four-day summer vacation with his wife, a college student daughter and a middle school student son. With a firm expression for one hour, the whole family experienced the history of forced labor all over with their eyes and ears.

-- Sick memories brought back by multimedia --

The museum's tour begins with a walk through a dark tunnel of memory. On the wall, the animation of walking comfort women and forced workers unfolds to the reading of stories about In Jae-ung, who was drafted as Japan's notorious suicide military squad (Kamikaze), and a young worker who was taken to Hokkaido, Japan at the age of 15.

Passing through the tunnel, you will see a box full of labor notebooks, and the last family photo taken with a son, who was drafted for the Japanese military, can be seen.

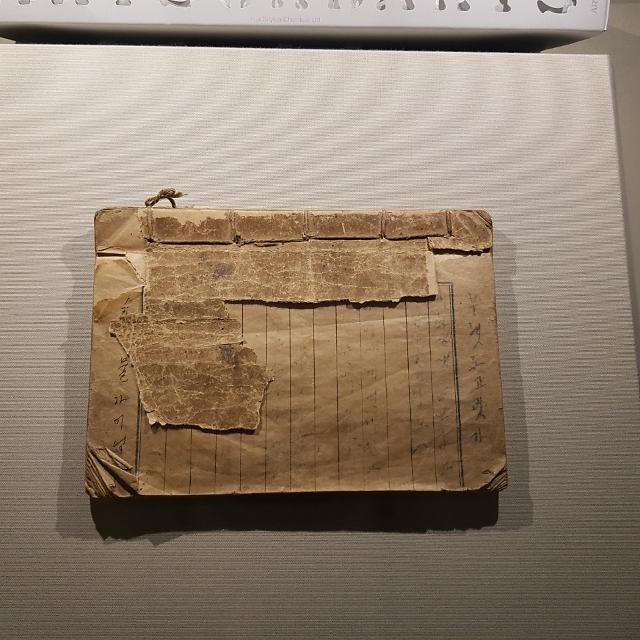

The memorial museum in Busan displays a small notebook written by Kang Sam-sul, who worked as a coal mine worker in Hokkaido. It is "The Song of Joys and Sorrows in Hokkaido." [Photo by Lee Sung-jae ]

One of the most eye-catching exhibits was a small notebook that was torn to shreds. It is "The Song of Joys and Sorrows in Hokkaido" written by Kang Sam-sul, who worked as a coal mine worker in Hokkaido. "As our home in Joseon (Korea) has dinner and night, my body is here in the endless depths of the earth, going through hardships day and night as such." That is the only piece of literature left by the victims of forced labor.

"Old Japanese military uniforms catch my eyes. It was too small even though it was small. The face of a mid-teen boy, who would have had a fluffy backstabbing fur, wavers in front of my eyes."

The set that recreated a mine and poor accommodations during the Pacific War was vivid. It even recreated people who had to work all day with a bent in a slanted shaft, and the scene of an ankle barely out after the collapse of the shaft.

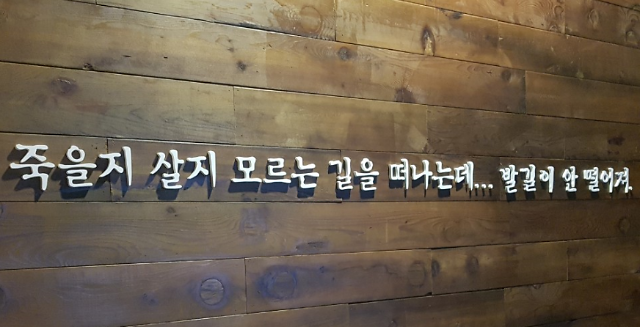

Words on the wall of a memorial museum in Busan read "Going on a road I don't know if I'm going to die or not, I can't get anywhere." [Photo by Lee Sung-jae]

Through old telephones, visitors can listen to the voices of those who were forced to work. There are detailed data and explanations on Ukisima, a Japanese navy transport ship which sank with some 7,000 Koreans aboard due to the explosion which was unknown in reason on August 24, 1945. Various photos are displayed tightly on one wall spanning three floors.

Five birds fly over the 5.7-meter-high memorial tower at the park built on the top floor of the museum. The victims of forced labor, who used to miss their hometowns while working in Japan as well as other faraway places like Sakhalin and the South Pacific, say they want to be fluttering birds.

A 5.7-meter-high memorial tower stands at a park built on the top floor of the memorial museum in Busan. [Photo by Lee Seung-jae]

-- War, which is oblivious of the past, ends up in death --

Forced labor by Japanese imperialists was all carried out by law. After the national mobilization act in April 1938, a total of 15 laws were enacted for forced mobilization, including the national occupation ordinance (1939), the ordinance on comfort women (1944), and the ordinance on work by students (1944), which mobilized all the manpower and materials on the Korean Peninsula until Japan's defeat in August 1945. They say mobilization, but it was forced exploitation.

The number of Koreans who were forced to work stands at 7,827,355, including duplicates, one in every three people who lived at the time on the Korean Peninsula with a population of 26,361,401 in 1942. In other words, all but children and the elderly were forced to work. Some 200,000 young Koreans were forced into the military while 7,554,764 people were mobilized for forced labor on the Korean Peninsula and in Japan and occupied areas.

The number of young women, who were drafted from colonies such as South Korea, China and Taiwan for sexual slavery at Japanese military brothels after the Japanese Empire invaded Manchuria in 1931, is estimated to be from 30,000 to 400,000

Recalling the terrible memory of World War I and II, George Santayana, an influential American philosopher (1863~1952), said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

However, the government's support for remembering the past is embarrassing. Only 10 million won is earmarked for the museum's annual purchase of historical materials. It's far short of buying a single memo with a Japanese-language coal mine term written in Korean. It goes without saying anything else, such as the budget for the foundation and the memorial museum, and the treatment of employees.

Santayana has also left such a famous saying, "Only the dead have seen the end of war."

If the philosopher's two famous words above are combined, that fits perfectly with the imminent war against Japan. There is nothing but death at the end of the war waged by those who do not remember the past.